Universities are known as liberal institutions. They are usually urban and their student populations are both highly educated and traditionally politically active. However, they are also places of privilege: attendance at university is more accessible to those from privileged socio-economic backgrounds, and there is a problem with gender imbalance among academic staff. I attend university in Ireland, and I can see how this lack of women in high-profile positions directly affects the education I receive.

The Higher Education Authority (HEA) of Ireland released a report on the 2015-16 academic year, with a follow-up report due in 2019, examining women’s position in academia. It found that although women made up roughly half of lecturing staff in Ireland that year, only a shocking 19% occupied academic professor positions. (This was shocking to me when I first encountered the statistic, but is not unusual in Europe in general). In non-academic staff, women were 62% of the workforce but men held 72% of the highest paid positions. A woman has never been president of a university in the Republic of Ireland.

It can be clearly seen, therefore, that the issue is not just getting women jobs in universities, but also helping them to advance. The HEA report states that the limits to women’s advancement were not due to a lack of talent or drive, but due to factors “conscious and unconscious, cultural and structural” not experienced by men in the same position. It points out that international evidence has shown that progress towards equality is “not automatically linear or inevitable”, but that gender balance when achieved is beneficial to organisations and correlates positively with improved performance. I use Ireland as an example, but it is important to note this is an issue across the world: in 2014, for example, only 20.9% of senior academics and 20.1% of heads of higher education institutions in Europe were women. In the U.S., women held 48.9% of tenure-track positions in 2015 but only 38.4% of actual tenured positions.

The lack of women in senior positions in universities indicates a lack of diversity, reduces other women’s chances of career advancement within these institutions, and can give rise to a male-dominated, misogynistic culture which further hinders progression. It also sends a message to female students about what they can realistically achieve in the world, and to male students about what they are entitled to. (Students can avoid taking messages like this one on board, and this is where the tradition of student activism and political awareness is beneficial, but they exist all the same.) This is important because university degrees bestow all kinds of privilege and university students will most likely form a large part of the next generation of politicians and CEOs. If they consume discriminatory messages, they may carry that prejudice into later life and into the workplace. One of the significant points made in the HEA report is that “education plays a vital role in the socialisation of citizens into an expectation of certain roles as ‘women’s work’ or ‘men’s work’.” While there are barriers to the career progression of women in all kinds of industries, as young people in Europe we must be particularly aware of this issue with regard to universities, because it affects the education we are receiving right now.

I am in my second year of a joint History and English Literature degree. At the end of this academic year, in my English course I will have studied the literary works of 62 men and only 26 women. (My focus in this article is gender imbalance, but it is important to note that those contained within a single lecture on Afromodernism, a single module on post-colonial literature and two slave narratives) Furthermore, women’s work is sometimes included only to address so-called women’s issues – despite the overall lack of female representation, I have now studied Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman twice. Even in the arts, which have a higher proportion of female academics than STEM subjects, the voices and stories deemed worthy of study are predominantly male. Low numbers of female staff and low representation of female writers are both part of the cultural norm which makes it standard to see few high-profile women throughout academia. These are both symptoms of the same issue. Therefore I believe an improvement in one area (a greater number of female staff) would lead to improvement in the other.

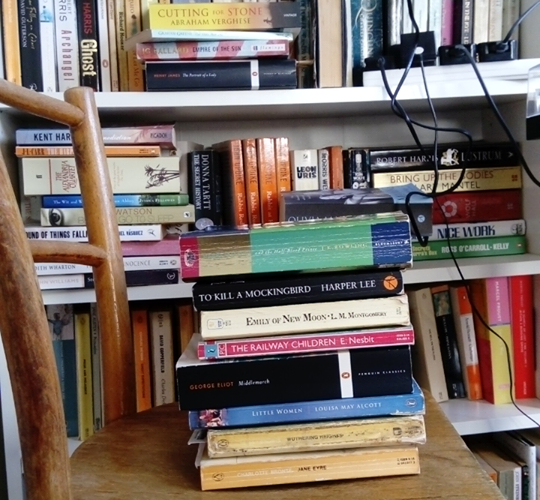

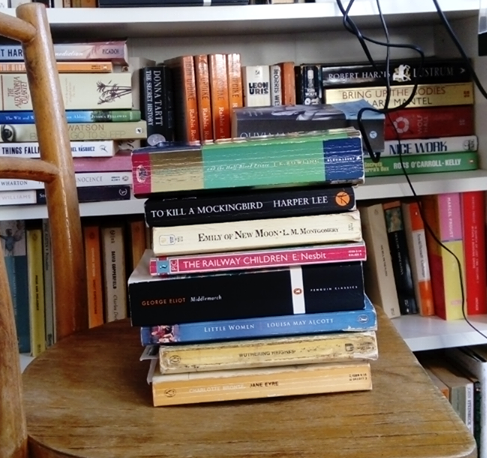

I understand that there are some practical reasons for the disparity in authors studied: because female authors have traditionally received less attention, there is less secondary material focusing on their work, making it difficult for students to research them. I also understand that a course focusing on Victorian literature (for example) must include the heavyweights such as Charles Dickens, and I appreciate that when studying more recent literary movements, the gender balance of authors is often (but not always) more representative. But a lack of female writers can also perpetuate the harmful ideas of the period being studied. For example, in the Victorian period, women wrote huge amounts of literature that was highly popular, but these were looked down on as commercial rather than seen as art; they were seen as less worthy or less literary or less interesting. The works we now consider to be the greatest of the period are largely by men. The women whose work receives recognition today are, strikingly frequently, the ones who used male pseudonyms (the Brontë sisters, or Mary Anne Evans, better known as George Eliot, for example). These ideas persist to this day, in that women are huge writers and consumers of fiction, but books by men or featuring male protagonists are statistically more likely to be recognised through modern literary awards.

This is not to say that this perpetuation of privilege has been done deliberately or maliciously, but to point out that we as students must think actively about the way we are being taught, or not being taught, or else our education in liberal universities may further reinforce ideas which lead to discrimination. If, as in this example, the number of women deemed worthy of study is so significantly less, we must be aware of the biases of the period being studied and also of the biases which persist today (such as the lack of high-profile female staff in universities) which make writing by men the status quo. We must be aware of the ways in which historical oppression reappears in our learning. Otherwise we risk taking its messages on board; in this example, we risk perceiving work by women as actually, inherently inferior.

*

In November 2014, Micheline Sheehy Skeffington won €70,000 from her former employer, NUI (National University of Ireland) Galway, because they were found to have discriminated against her for promotion on the basis of her gender. This was heralded as a landmark victory. Since 2014, there have been moves within Ireland to address the issue. The HEA’s comprehensive report in 2016 laid out a plan of action. The very existence of this report and plan is encouraging, but change has been slow. Sheehy Skeffington wrote in 2017 of her disappointment at the lack of meaningful improvement. It is clear there is much work still to be done.

While I hope for continued improvement in the future, it will take time; I doubt there will be significant change before I finish my degree. As young people in Europe, we must be aware of the issue of gender imbalance in our academic institutions, but we must also actively think about how it affects us right now and how it impacts the education we receive.

About the author:

Carol McGill (19) participated in the “My Europe” workshop in Dublin in 2014. She is a student of History and English Literature and loves to write in her free time. Carol also enjoys drama and reading. After completing her degree she would like to be involved in promoting human rights and preventing discrimination.

Carol McGill (19) participated in the “My Europe” workshop in Dublin in 2014. She is a student of History and English Literature and loves to write in her free time. Carol also enjoys drama and reading. After completing her degree she would like to be involved in promoting human rights and preventing discrimination.

References

- Full HEA report: http://hea.ie/assets/uploads/2017/06/HEA-National-Review-of-Gender-Equality-in-Irish-Higher-Education-Institutions.pdf

- Statistics on female staff in higher education: http://www.catalyst.org/knowledge/women-academia#footnote13_6mk41tz

- Statistics on gender bias in modern publishing: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jun/05/kamila-shamsie-2018-year-publishing-women-no-new-books-men

- Details of Micheline Sheehy Skeffington’s case against NUI Galway: https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/people/micheline-sheehy-skeffington-i-m-from-a-family-of-feminists-i-took-this-case-to-honour-them-1.2027451

- Sheehy Skeffington writing in 2017: https://villagemagazine.ie/index.php/2017/01/gender-isory/